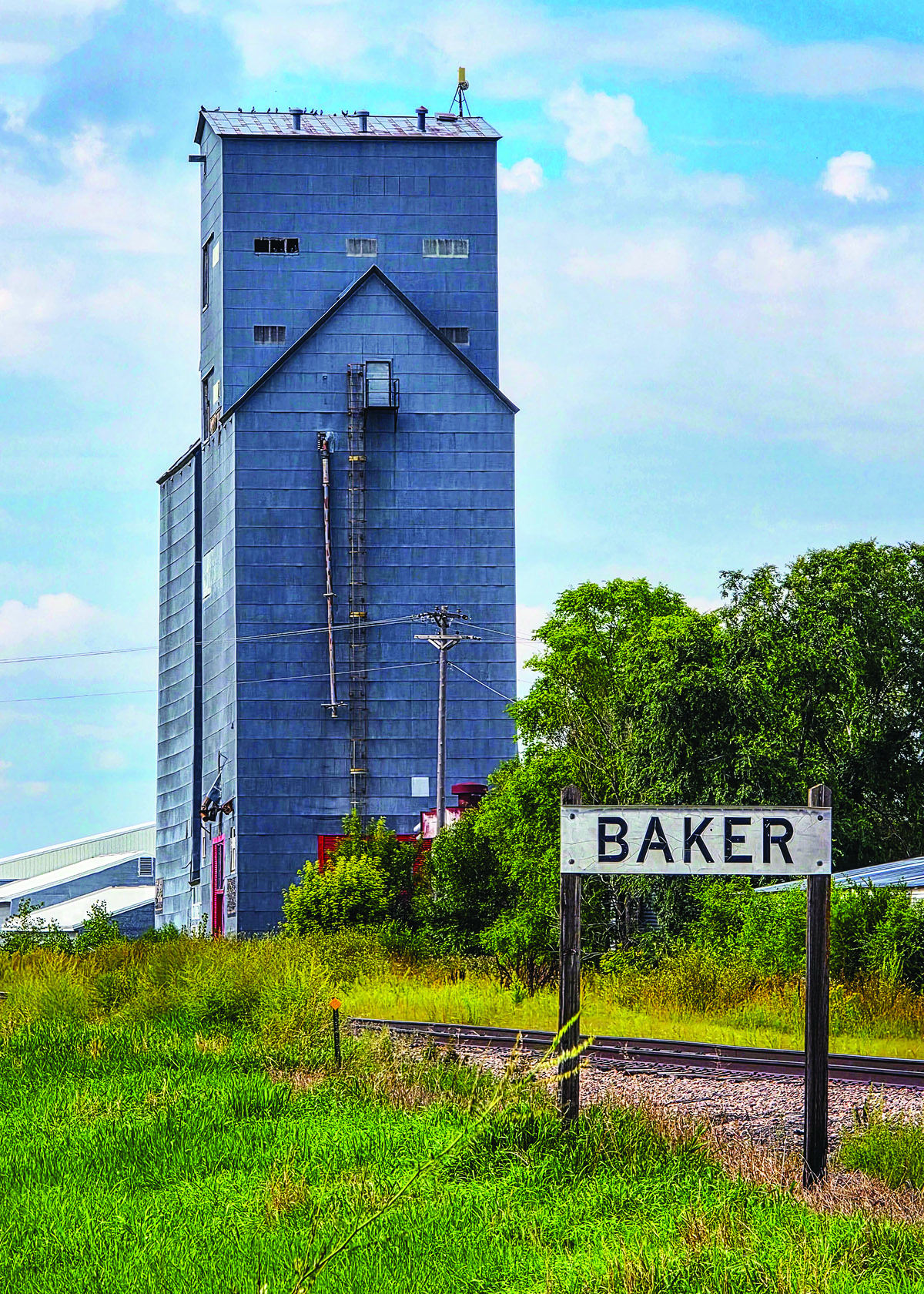

- The old Red River Grain Company elevator in Baker, Minnesota. (Photo/Nancy Hanson.)

- One of several lounge areas overlooks the prairie west of Dahms’ elevator. (Photo/Nancy Hanson.)

- A funky lobby, including a spiral slide and a wall’s worth of vintage skateboards, is inside the door where grain trucks once entered to dump their loads. (Photo/Nancy Hanson.)

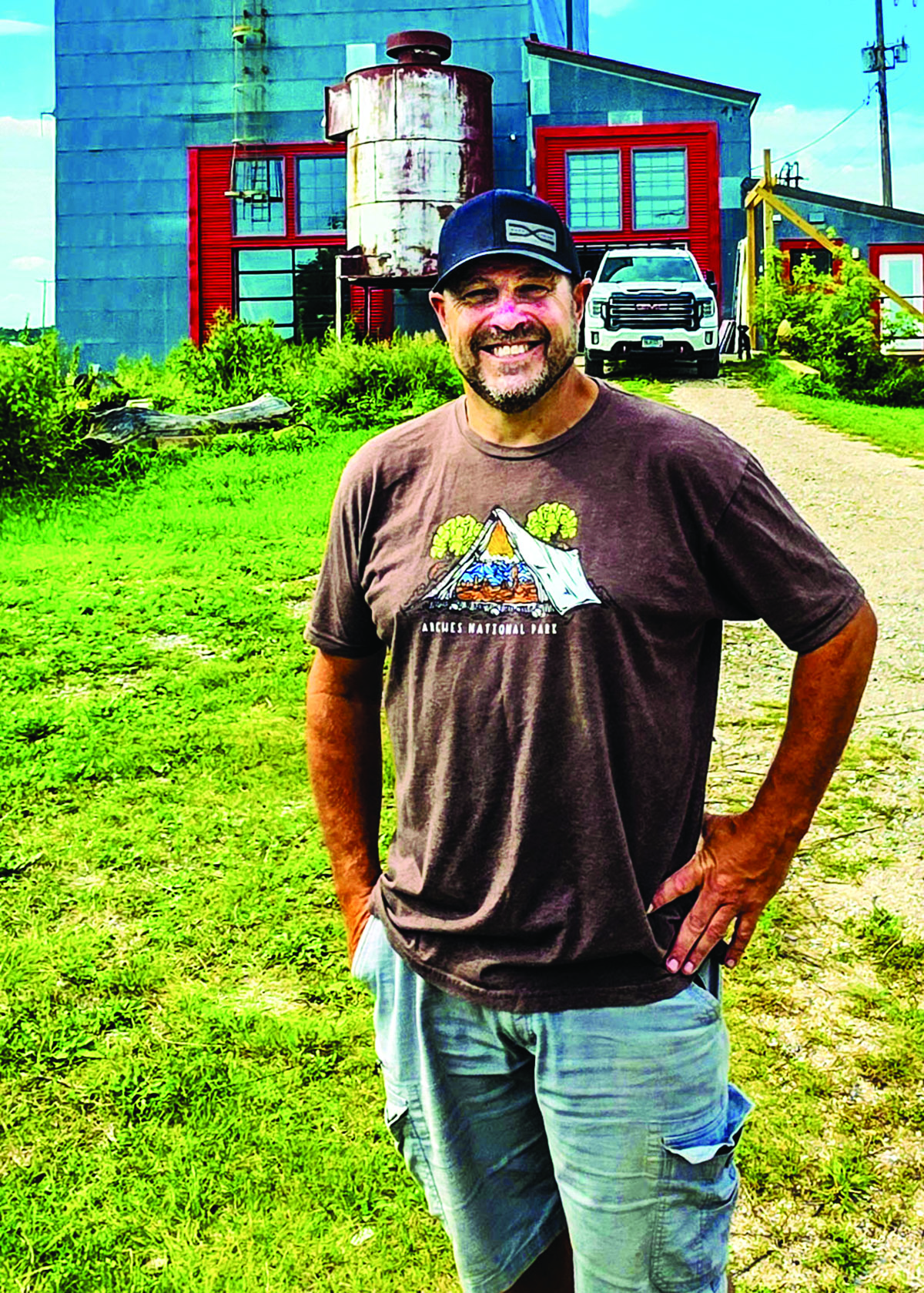

Architect Scott Dahms purchased the long-empty Baker elevator nine years ago and has worked on finding adaptive uses ever since.

Just Down the Road

Nancy Edmonds Hanson

Architect Scott Dahms was cruising rural Clay County when a vertical point on the flat, flat landscape caught his eye.

“I didn’t know anything about Baker,” he says now. “And I didn’t know anything about elevators. But I’m kind of a dreamer and knew it had potential. I wanted it.”

After bargaining down the owner’s asking price, he bought the dilapidated landmark for a rock-bottom price. He has spent the past eight years weighing ideas to give new life to the long-abandoned Red River Grain Company elevator beside Highway 52 – to not only turn a profit, but help revitalize the tiny unincorporated village, population 45, around it.

Scott thought he had found a winning formula in Minnesota’s two-year-old measure to legalize growing, processing and selling cannabis. He envisions a destination that would draw customers to the roadside spot halfway between Sabin and Barnesville, combining a retail shop, an indoor lounge and small event center and vertical space to grow the high-value crop itself in the second tower on the property.

His plans received pre-approval from the Office of Cannabis Management in St. Paul. Securing a location was the second step; he hoped to receive one of the six cannabis permits to be issued by Clay County for his adaptive use of the Baker elevator.

Then came the approach to the Clay County Planning Commission for a conditional use permit. The tiny settlement is zoned ACS – “agricultural service center.” Unlike the “highway commercial” areas, almost all located along Highway 10, county regulations mostly limit the out-of-the-way locale to businesses serving farmers. However broadening the permitted types through exceptions to the rules – CUPs – is not uncommon.

Two other issues raised after his presentation would also require a variance – that a commercial enterprise be 500 feet from the nearest residence, and that the entrepreneur own at least one acre of land. Scott’s property is a little less than half an acre. The township, he says, is willing to sell him the weed-infested ground to the south along the railroad line, and “the neighbors we’ve talked to here are overwhelmingly in favor of what we’re doing.”

But when his request was reviewed by a subcommittee of the Clay Planning and Zoning Commission in late August, it was turned down. He will go before the full Planning Commission Sept. 16, hoping for a reversal of that vote.

The delay plus a potential appeal could put plans for the shop, entertainment center and cultivation in jeopardy. “We’re up against a timeline,” Scott says. “Clay County will only issue six cannabis permits, based on its population. Two are already assigned, and other applicants are waiting in line. Once those six locations are in place, we won’t have this opportunity again.”

Parts of Scott’s elevator are already up and running. He operates a popular bed-and-breakfast there, combining comfortable accommodations with fun, funky décor reminiscent of the skateboard culture he enjoyed in his younger days. The suite can accommodate as many as 20 guests and, he says, is occupied nearly every weekend. “It brings in some income, but not enough to rehabilitate the rest of the building,” he reports.

That’s where growing legal Minnesota cannabis comes in. The second elevator next to the one he’s been fitting up offers perfect space, he says, for indoor cultivation. “You couldn’t break even with any other crop, like tomatoes or other vegetables,” he explains. “But the high value placed on every pound of cannabis, at something like $2,000 per pound, makes this plan feasible.”

Would Baker and Clay County benefit financially from Scott’s plan? While all sales tax on cannabis products goes directly to the state by law, he points out the enterprise would offer financial benefits to the area, including property taxes on the rehabilitated enterprise.

Sabin and Barnesville, each six miles away, would also benefit from downstream sales. Baker itself, settled 145 years ago, once had a train depot, two stores, a post office, a hotel, a school, a bank, a lumber yard and an implement dealership, which also sold cars. Today it has no operating businesses of any kind. He predicts, “People who visit us will need to buy gas, food and alcohol somewhere,” he notes. “They’ll shop just down the road. Everybody will benefit.”

While Scott awaits the official verdict on the conditional use permit he seeks here in Clay County, he’s already looking further down the road. Last week he purchased an empty welding shop in Pelican Rapids, which lies next door in Otter Tail County. While it’s four times as far from Fargo-Moorhead as Baker – 48 miles versus just 12 – the lakes-country town appears more amenable to the destination shop and nightclub he envisions.

But he reasserts, “I’m not giving up here. I’m going to keep after Clay County, too. I haven’t found any other plan for adaptive use of a grain elevator anywhere else. My Baker plan would be one of a kind.

“What else is going to happen to these old elevators? Unless we find adaptive uses, they’re just going to stand here until they fall down, or burn down. When a visionary is ready to put down his money, sweat and tears into creating a new use, it just makes sense to give it a chance.”