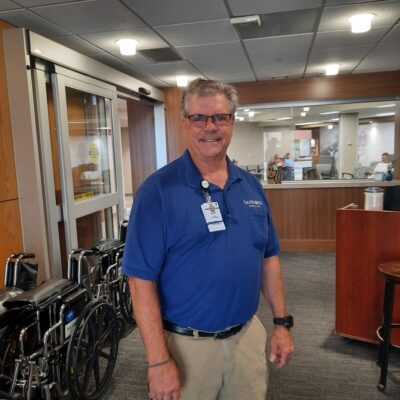

- Valet Scott Erickson said the simplest gestures can bring a smile to a patient’s face. (Photos/Michael Stein)

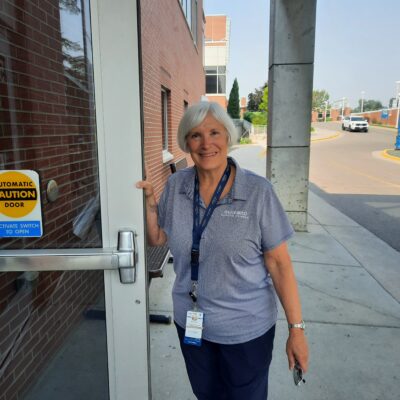

- Paula Bjerk brings empathy and compassion to her job as a Sanford greeter.

- Chris Hames says this team is “a dream to manage.”

- Sanford valets do everything they can to make patients comfortable as they enter the building.

A valued service with a human touch

Michael Stein

They’re not there to take your pulse or check your blood pressure or oxygen level. They won’t even ask for your last name and birthdate. While not medical professionals—although some may have some background in the health field—the greeters and valets at Sanford hospitals and clinics provide a vital and heartfelt service: to help patients feel more at ease and maybe even bring a smile to their faces.

These folks, present in facilities throughout the Sanford system, are there to guide patients and answer questions as they arrive for an appointment or visit a patient. One group in particular takes this service to a different level.

The greeters and valet service providers at the Sanford Roger Maris Cancer Center in north Fargo are dedicated to bringing needed brightness to patients facing difficult situations. In short, it’s a labor of love.

“Initially, this was our only valet team,” said Chris Hames, facility operations manager who oversees the valet and team volunteer teams. “We have 30 employees in four valet programs here in Fargo. This was the catalyst for the larger program. It was so successful with its impact on patients that it quickly became a model for how we wanted people to enter our buildings and the experience they have when coming for services.”

There is no formal welcoming process—it’s more like a warm greeting you’d receive from a gracious aunt or uncle. “Our role is to bring some normalcy into our interaction, which is not what patients have when they meet with the medical staff,” said Hames, who has prior experience as a social worker.

One of the newest members of the team, Scott Erickson, is retired from the grocery business and also serves as a Cass County jail chaplain one day a week. “It’s been a great job,” he said. “I’ve learned from my work in sales that to make something successful, people want a positive initial experience. When we’re helping bring people into the cancer clinic, it’s often not in a good way. So, you try to lighten things up as you greet them and take the tension out of the situation.”

Erickson added that it’s usually the little things that can make a big difference for patients coming to receive cancer care. “We’ll help them get out of their vehicle and into registration. In the process, we try to sidetrack them from focusing on their treatment and make them more comfortable. The valet service is a perk and people just love it. We get compliments every day, and people actually want to give us tips. We tell them to treat themselves or their family instead.”

Greeter Paula Bjerk, who has been a greeter for three years at different times, worked full time for 15 years in the Eye Care department before her retirement. “When I decided to retire I didn’t want to do it cold turkey,” she said. “And I wanted to do something meaningful.”

Bjerk’s husband received treatment at Roger Maris for 10 years before his passing. “He loved coming here because of the greeters. There’s a lot of empathy and compassion passed along by the valets and greeters, who are a tight-knit group.”

Erickson concurs. “It’s a great team. I would say this place is revered and I feel fortunate that Chris contacted me about the job. Yes, it can get very busy, but everyone knows their role and eventually things get taken care of, and people are on their way and cars get parked.”

Hames emphasized that compassionate empathy is a prerequisite for new greeters and valets at all locations, but especially at Roger Maris. “People are coming here for answers and hope, and that’s something we can be part of—part of something bigger. I heard a patient say we are the only normal thing they have going when they come here. They don’t want to talk about their diagnosis; they want a distraction from their diagnosis.”

Bjerk cited long-time valet Chuck Wickenheiser for providing that compassionate empathy when her husband, Gregg, was receiving treatments. “Chuck remembered his name, which we can’t always do with so many patients coming in,” Bjerk said. “We try to remember their names as much as possible.”

Hames recalled an instance when Wickenheiser went well above and beyond the normal call of duty: “We had a patient that had gotten sick in her car. Our policy is that we don’t park cars that contain bodily fluids. Chuck gowned and gloved up and cleaned her entire car. I’ve shared that story about the power of a small touch in someone’s life many times.”

Functionally, Hames said, the valets’ job is getting patients into the building and parking their cars; the greeters’ job revolves around procuring wheelchairs when needed and getting them through the building and to their appointments on time. “And welcoming is part of everyone’s job,” Hames said. “Often, for instance, you’ll see Paula gone from the front area because so many patients need to get to other parts of the building. The others are pretty much stationed in the front area.”

“Paula and the other greeters help us out many times when we get really busy,” Erickson said. “They’ll help write up the ticket for the car, and if Paula is up on third floor, one of us will help with getting other patients around the building.”

Hames said turnover is not an issue with the teams. “We have mostly pre- and post-retirement individuals who want meaningful work—and they’re a dream to manage. For the most part, they stay until they can no longer work.”

Within four clinics, three hospitals, and the emergency center, there are about 100 guest service providers comprising clinic greeters, welcome desk staff at hospitals, and four valet teams.

“It speaks to Sanford’s commitment to having a greeting process,” Hames said. “The payback is having frontline people help patients get through the door. Much of our recruiting is by word of mouth. I keep an informal list of people who have expressed interest in a greeter or valet position and are looking for particular shifts or number of hours. Most of the positions are part-time.”

There is no intense interview process or formal training for greeters and valets. “We look for people skills,” Hames said. “I don’t ask open-ended questions because I don’t care how you interview, as long as you can have a conversation with me.”

“But you’re easy to talk to,” Erickson interjected, adding that the skills he learned during his business career transfer well to his current role. “You don’t think of yourself first. You think of others and the rewards come.”

Interacting with people during a dark time in their life is a daunting task. The greeters and valets know this very well but use whatever tools they can to clear away at least a little of the darkness.

“Everybody’s trigger can be tripped,” Erickson said. “It’s often something simple and random like talking about the music you might hear coming from their vehicle. It’s anything you can find to put people more at ease in a difficult situation.”

Bjerk, who has a long history with Sanford, finds many ways to genuinely get a conversation started. “We talk about grandkids, sports, and many other things.”

“They see how strong people can be,” Hames said. “They’re coming in with heavy diagnoses and they’re still laughing and smiling. It makes you think about how you can still find happiness in dark times. It’s inspiring.”

Bjerk and Erickson said they intend to keep doing this rewarding work until they’re physically unable to.

Quoting poet Maya Angelou, Hames said, “People are not going to remember you for what you said or did, but how you made them feel.” Erickson added, “Kindness doesn’t have to be complicated, whether it’s holding a door for someone or smiling and saying good morning.”